कट्टर मुस्लिम सोच व् लोग तो अब जग विदित है . जो नहीं भी जानते उन्हें इस्लामिक आतंकवादी नहीं छोड़ रहे . चाहे कितना भी बुरा लगे , गैर इस्लामिक संसार मैं आतंकवाद ही इस्लाम की सबसे बड़ी पहचान बन कर उभरा है . पर इस अँधेरे मैं आशा की कुछ किरणें दीख रही हैं . हर देश मैं कुछ लोग इसका विरोध कर रहे हैं . परन्तु मलालाओं की संख्या नगण्य है .

कट्टर मुस्लिम सोच व् लोग तो अब जग विदित है . जो नहीं भी जानते उन्हें इस्लामिक आतंकवादी नहीं छोड़ रहे . चाहे कितना भी बुरा लगे , गैर इस्लामिक संसार मैं आतंकवाद ही इस्लाम की सबसे बड़ी पहचान बन कर उभरा है . पर इस अँधेरे मैं आशा की कुछ किरणें दीख रही हैं . हर देश मैं कुछ लोग इसका विरोध कर रहे हैं . परन्तु मलालाओं की संख्या नगण्य है .

सन १३ ०० से १९६० तक इस्लाम शांत था . तो फिर यह आतंकवाद का भूचाल कैसे आया ?

वस्तुतः तेल के दाम बढ़ने से मुसलामानों के सोते ख्वाब जग गए . वह पुनः विश्व पर राज करने का स्वप्न देखने लगे .परन्तु शक्ति अब पश्चिम के हाथ मैं थी . इस्लामिक आबादी भूल गयी की तेल की खोज मैं उसका हाथ नहीं था . यह तो पश्चिम की दें थी . उनकी समस्त ताकत पश्चिम की भेंट थी .

अब क्या भविष्य है . अकबर ने भी धरम को सहिष्णुता की और मोड़ने की कोशिश की थी . पर राजा होने के बाद भी वह सफल नहीं हुआ .  पश्चिमी सभ्यता गिरती आबादी व् महिला मुक्ति आन्दोलन के कारन अब पतन की और अग्रसर हो चुकी है . अब पश्चिम मैं इस्लाम को रोक पाने की शक्ति नहीं है . अन नए कृसदे शुरू करना उनके बस की बात नहीं है . आतंकवादी इस बात को जान चुके हैं . कुछ बुश ,सरकोजी व् थैचर सरीखे नेता और हो जाएँ तो शायद विश्व इस त्रासदी से बच जाये .

पश्चिमी सभ्यता गिरती आबादी व् महिला मुक्ति आन्दोलन के कारन अब पतन की और अग्रसर हो चुकी है . अब पश्चिम मैं इस्लाम को रोक पाने की शक्ति नहीं है . अन नए कृसदे शुरू करना उनके बस की बात नहीं है . आतंकवादी इस बात को जान चुके हैं . कुछ बुश ,सरकोजी व् थैचर सरीखे नेता और हो जाएँ तो शायद विश्व इस त्रासदी से बच जाये .

कुछ चुनिंदे खुले दिमाग के लोग सिर्फ अखबारों मैं लेख लिख सकेंगे पर किसी कट्टरवादी आन्दोलन को रोक पाना उनके बस की बात नहीं है .

संसार को इस सत्य को जान कर और ध्यान मैं रख कर अपनी रक्षा के बारे मैं सोचना होगा .

Beyond stereotypes: Stories of the brave

http://www.dailypioneer.com/columnists/edit/beyond-stereotypes-stories-of-the-brave.html

There are hundreds of people in Islamic countries like Pakistan who have been courageously challenging religious fundamentalists and their agenda of violence. But their battles are largely hidden from the world

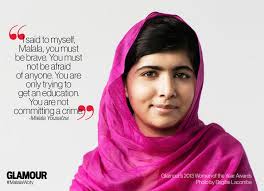

Malala Yousafzai has become the global face of resistance to Islamic fundamentalism in Pakistan. But there are many more ordinary citizens of that country who are constantly standing up to such terror, and while their struggles are not as well known, their zeal and commitment to the creation of a society that will not bow before the violent fundamentalists, are remarkable.

Author Karima Bennoune has brought to us the stories of these brave men, women and children in her book, Your fatwa does not apply here. It shatters the myth that most people in Pakistan are not just reconciled to the rampage of the Islamist brigade but are also complicit in it through their silence. Not only have these courageous people been speaking out but they have been doing so at enormous risk to their lives and to the lives of their family and friends. They have persisted despite being attacked, and despite the deaths and injuries that those who were associated with them have suffered in recent years. Bennoune dispels the stereotypes and strengthens the belief that all is not lost yet, and that the fundamentalists cannot silence the voice of reason.

Bennoune grew up in Algeria in the midst of terrorist violence, where the Islamists on more than one occasion tried to intimidate her father, who had been constantly speaking out against them. Professor Mahfoud Bennoune had been an outspoken critic of both the successive Algerian Governments and the armed fundamentalists who had opposed these regimes. That should have made him neutral, but it did not. The militants were baying for his blood. The author narrates an instance where the Islamic Salvation Front made its intentions clear. “My father’s teaching of Darwin had already provoked a classroom visit from the head of the Islamic Salvation Front, who denounced him an advocate of ‘biologism’ before Dad ejected the man.” He remained in the shadows of death from thereon. He did not revise his views, but the only compromise he made was to give up his residence and teaching job at a university and relocate.

The book is not about Bennoune or her father. It is, as mentioned earlier, about the hundreds of ordinary people who have shown similar exemplary courage in the face of Islamists. It is, for example, about Faizan Peerzada and his daughter Nur who managed the Rafi Peer Theatre Workshop. Named after Nur’s grandfather and playwright, Rafi Peerzada, the objective of the theatre is to promote Pakistan’s rich art and culture. Commendable as the activity is, it is also innocuous enough not to attract the attention of the Islamic moralist brigade — but it did.

In 2008, when the group was engaged in preparations for the annual World Performing Arts Festival in 2008, fundamentalists set off bombs at the site. A few months earlier, the restaurant at the Rafi Peer’s main offices was blown apart. The message that Faizan and company got was that they must end such ‘nonsense’ which went against Islam, but they ignored it. In virtual defiance, in 2010, they organised the Ninth Youth Performing Arts Festival in Lahore. They couldn’t be silenced.

Faizan (who died of a heart ailment in December 2012) tells the author, “If we bow down to the Islamists, then everything is going to be rolled back, and they will always have their way… We’ll just be sitting ducks in a dark corner.” The Rafi Peer group was unwilling to be those sitting ducks.

Faizan is not alone in Pakistan. Bennoune narrates the experiences of Madeeha Gauhar, director of Ajoka Theatre Company. The author informs that Ajoka is even more outspoken in stating its opposition to the fundamentalists than the Rafi Peer outfit. Madeeha calls her venture a “theatre of resistance”. It was in the forefront of such resistance against Zia-ul-Haq’s dogmatism but has also taken on non-Government Islamists as well. In 2007, she staged a musical whose title as well as content outraged the fundamentalists. Burqavaganza was a ‘love story in the time of jihad’ and deeply contemptuous of the mullah brigade as well as terrorism. It showed burqa-wearing fundamentalists terrorising young couples who wanted to be together. The play ends with a couple being lashed, stoned and finally being hanged, after being condemned for “loving each other, with being beautiful, with being joyful”.

The couple may have died onstage but the spirit of freedom to choose without the moralists breathing down the neck, remains intact in real life. It’s from the Ajoka Theatre Company that Bennoune has picked the title for her book. In a play, where Islamists swoop down on a group of followers of the mystic Bulla Shah, who are singing in praise of universal goodness, one of the singers rebuffs them with the line, “Your fatwas do not apply here”. It is part of the script but packs a punch that can change society.

And then there is Diep Saeeda, a peace activist whom Bennoune met in Pakistan. Saeeda narrates an instance when a caller threatened her with a visit to her place with a suicide jacket. She replied, “I don’t care. Come with the suicide jacket. Bring more suicide bombers as well.” She later received an email which announced that she was a “threat to the Muslim umma”. Her crime was that she had organised a rally against the country’s blasphemy law and the killing of a Pakistani Christian, Asia Bibi. Saeeda’s resolve is no ordinary act of defiance; only months before that protest rally in Lahore, a triple-suicide blast supposedly engineered by the Taliban had claimed 25 lives. It was a message for the likes of the activist to behave or else…

It is not in Pakistan alone that there are strong voices speaking out against the Islamists. As the author observes, they are coming from across the Muslim world, be it Algeria or Libya or Egypt. Bennoune says that “many groups in Muslim majority societies regularly denounce terrorism, even when doing so is dangerous and receives minimal international publicity. In the West, it is sometimes assumed that Muslims generally condone terrorism. The Right often presumes this because it views Muslim culture as inherently violent. The Left at times imagines this because it interprets fundamentalist terrorism as simply a reflect of legitimate grievances.”

But the resistance to Islamist extremism has to grow stronger in the Islamic world. The author observes, “Many people of Muslim heritage — though not enough yet (italics provided) — are ardent opponents of fundamentalist violence and for very good reasons… Those most commonly on the receiving end in recent years have been people of Muslim heritage killed by Muslim fundamentalists.” She rounds off by pointing out that “between 2006 and 2008, fully 98 per cent of Al Qaeda’s victims were of Muslim heritage.”

Karima Bennoune has through her book contributed to the struggle against Islamic fundamentalism. She approvingly winds up with the quote: “Hush up the truth, hush up the crime.” That also applies to other things beyond Islamist fundamentalism, in India and elsewhere.