Muslim Ethos In Indian Cinema

Pankaj Jain blog

http://pankajaindia.blogspot.co.uk/2008/10/muslim-ethos-in-indian-cinema.html

Saturday, October 04, 2008 Indian Express Muslim Ethos In Indian Cinema —Iqbal Masud In term of quantitative output – more than 800 films a year – the Indian cinema industry is the largest in the world. A major portion of the films constitute ‘popular’ of ‘commercial’ cinema. This term is not to be understood in any derogatory sense. Cinema is the main entertainment of the Indian masses and has been so since the 1930s. It has created archetypes, myths, icons which have dominated the Indian consciousness – and the Indian unconscious for the last 50 years. It’s a major source of collective fantasy.

There is another important aspect of Indian cinema. It caters to the needs of a population dazzlingly diverse in language, religion and culture. Today what is called the ‘regional’ cinema is as important as Hindi cinema. But Hindi cinema (with which this article will be concerned) was the primary source of themes and styles at least till the late 70s. It was in the domain of popular cinema that the diverse cultures of India met and negotiated their differences. They did not merge but they worked in harmony. In fact ‘harmony’ is the key world in India cinema. It is the one Indian cultural-industrial structure which has resisted separatism. It’s because of this element that Indian cinema has become over the past 50 years – despite its many distortions and contractions – a major instrument of national consolidation – a true unity in diversity. MIDBANNER To this ‘unity diversity’ the Muslim ethos in India has made a notable contribution.

What is the ‘Muslim ethos’ in India? Very briefly, one can answer this question at two levels:

a) ‘Classical’ or high culture – a mix of Arabic-Perso-Turkish elements in historical work, fiction, music and painting such as in the work of poets and novelists like Ghalib, (or today Ms Qurratulain Hyder), artists like Abdur Rahman Chughtai, or the Ustads in the field of music.

b) At a popular or folk level, the work of Urdu dramatists like Aga Hashr Kashmiri used in popular theatre of the 1930s; the Nautanki Folk-theatre culture of Uttar Pradesh, compounded of mythological and folk tales rendered in song-dance and rustic revues in a mix of ornate Urdu and dialect Hindi of north India; and the rich Qawwali musical tradition, sufic in origin and retaining traces of devotional and ecstatic singing today.

As far as cinema is concerned, both these influences are important. The Muslim ethos in Indian cinema was not represented by ‘Muslim’ artists alone. A host of non-Muslims like Sohrab Modi, Guru Dutt or Shyam Benegal can well claim to be part of the ‘Muslim’ ethos of north India. There was, and is, certainly a ‘Muslim’ ethos of Bengal and South India which is equally important. But that deserves fuller treatment elsewhere.

The point is that in the popular entertainment genre par excellence – cinema – the ‘Muslim ethos’ was an important element since the 1930s – the coming of sound. It diminished after 1947 but remains an important element today. In fact the persistence of the ‘Muslim ethos’ in Indian cinema today is one of the most hopeful signs of Indian secularism. Manmohan Desai, prolific maker of film hits and part creator of the Amitabh Bachchan legend (the superstar of the 70s who signified the new angry hero culture) has said in a recorded discussion: If the Muslims don’t like a film it flops’.

One of the most important elements of the Indian film is music. A great music director, Naushad, brought both the vigour of Uttar Pradesh’s folk music and the grace of the old UP Nawab Courts to his immortal music of the 40s and 50s. The dialogue of the 30s and 40s ‘Muslim socials’ was in Persianised Urdu but even in ‘Hindi’ films today the dialogue is in Hindustani – perhaps the only place where this ‘language’ is practiced with ease and confidence.

In this matrix of music and dialogue, ‘high’ and ‘popular’ Muslim cultures come together. As late as the 60s, a film villain traps a heroine by using a disguise and quoting Ghalib: ‘Badal kar faqiron ka hum bhes …’ Ghalib/‘Tamashai-I-abl-I-karam dekhte hain …’ (we put on the garb of a beggar to test the generosity of the rich). The audience understood and applauded the quote.

Today this delicate irony may not be understood. But in the ’80s this last couplet of Sahir Ludhianvi sung in a film called Laxmi went to the heart of the audience: ‘Halat se ladna mushkil tha balat se rishta jod liya/ Jis raat ki koi subha nahin us raat se rishta jod liya…’. (I could not fight circumstances I compromised/I made a pact with endless night). The couplet lit up the films; it also seemed like an epitaph on Sahir.

I take these two examples to illustrate the Muslim ‘ethos’ which E.M. Forster once described as an ‘attitude towards life both exquisite and durable’. This attitude is denoted by a cultural elegance, irony, stoicism, a throw away humour, and what is called ‘grace under pressure’. Certainly such an attitude could be trivialised. But supreme artists like Dilip Kumar, Meena Kumari, Nargis and Shabana Azmi brought to this attitude a meaning and individuality of their own.

It would be appropriate at this stage to look at the Muslim ethos in a chronological fashion modified by the need to pursue specific trends back and forth across decades.

Devdas – Entry of the Laila – Majnu Myth

The first dominant note of the Muslim ethos was struck not in any specific Muslim film or by a Muslim director but in the film Devdas directed by PC Barua (1935) based on a novel by Sarat Chandra Chatterji (1917). This tale of two small town lovers torn apart by caste and class has haunted Indian cinema down the decades up to date. There are two elements in Indian cinema well analysed in another context by psychiatrists Sudhir Kakar and John M Ross in Tales of Love, Sex and Danger (OUP 1986) as the Radha-Krishna and Laila-Majnu traditions. Radha and Krishna are the divine lovers in human form in Hindu mythology, and Laila and Majnu are passionate but doomed lovers in Arabic and Persian folklore and literature.

The Radha-Krishna tradition, say the authors, is an evocation and elaboration of here-and-now passion, an attempt to catch the exciting fleeting moment of the senses, not tragic but tender and ultimately cheerful. In the Laila-Majnu tradition, love is the ‘essential desire of God; earthly love is but a preparation for the heavenly acme; the challenge to rights of older and powerful men to dispose of and control female sexuality; the utter devotion of the women lovers to the man unto death; loving in secrecy and concealment, yet without shame or guilt’.

Both the elements are fused in Devdas. The Radha-Krishna element dominates the first half; the Laila-Majnu element the second. There are two features common to both traditions. The love is not ‘spiritual’ love but sexual love raised to a spiritual plane. Secondly, to quote the 13th Century Persian mystic poet, Rumi: ‘The house of love has doors and roofs made of music, melody and poetry’. This is the distinctive contribution of the Muslim ethos to Indian cinema – the mix of Rumi’s three elements. You can go from Devdas to Barsaat in the ’40s or Pyaasa in the ’50s; Chaudvin Ka Chand in the ’60s; Pakeezah in the ’70s; Sagar (with Kamal Hasan, Dimple Kapadia, and Rishi Kapoor) in the ’80s. There is the same hunting mix of the two great religious-cultural traditions of our land.

Pukar – The Rise of the Shahenshah film

Pukar (1939) directed by Sohrab Modi with dialogues by Kamal Amrohi was the first notable ‘Muslim social film’. It was cast, no doubt in the Shahenshah (King of Kings) framework. Mughal emperor Jehangir, whose queen Noor Jehan has accidentally killed a washerman with an arrow, is faced with a demand for retributive justice by the widow. The emperor himself should be killed so that the queen be widowed.

Today Pukar looks dated and rhetorical. Yet it is important to isolate some elements which continue to surface in one form or another in the coming decades, from the 40s to the present. One was the idealisation of ‘Muslim’ rulership as one based on equal partnership with non-Muslims (even of the lesser castes) and a rough-and-ready Rule of Law. The roots of the archetype of task a ‘rough diamond’ were created – though in the film the Muslims and their ‘partners’ the Rajputs were anything but rough. The basic ideal was one of directness of approach of life.

A second element was the elegance of speech and surroundings which became a marked feature of Muslim social’ – meaning films dealing with Muslim families and social problems which will be dealt with later.

A third element was the stress laid on Hindu-Muslim ‘harmony’. Jehangir’s Prime Minister is a Rajput who fiercely guards his independence.

Another Shahenshah film was K Asif’s Mughal-e-Azam (The Grand Mughal). In a sense it’s an extension of the Pukar syndrome. The legendary love of court dancer Anarkali for Prince Jehangir, the great Emperor Akbar’s son, has elements of mystical passion in it. Akbar, played with rhetorical flourish by Prithviraj Kapoor, represents the ‘needs of the State’ which triumphs over love. The film is not a ‘classical’ work but a massive cultural artefact made unforgettable by the splendiferous sets and the majestic singing of the classical maestro Bade Gulam Ali Khan.

Mehboob – The Rise of Radicalism

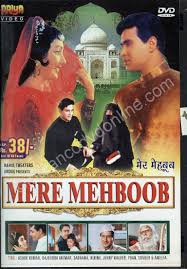

Filmmaker Mehboob Khan sprang from the soil of Gujarat and his early work possessed both the rawness and the strength of Mother Earth. The evocation of the cycle of seasons, the beauty of the long bullock cart caravans, the sensuality of the women and the depiction of the brutal strength both of nature and human oppression came spontaneously to him.

Mehboob made a large number of films on diverse subjects – social, romance etc. But, in my opinion, his major contribution to films rests on three films – Aurat (1940) later remade as Mother India (1957) and Roti (1942).

Aurat/Mother India, is, of course, the seminal film of India cinema. It is reckoned that Mother India runs every day in some theatre in some part of India. What accounts for its success?

There are elements in the films which go deep into the Indian psyche and touch a chord which no one has ever touched before or since. It would be simplistic to call it ‘patriotism’. It is the summoning up of an entire ambience – the ambience of the ‘lost’ India for millions of urbanites, a call to Indians from their past – not a noble past but a credible and genuine past.

Mehboob gave the archetypal ‘Mother’ myth to India cinema. She is not an a sexual but a full blooded woman and equal partner in her husband’s labours (a point acutely noted by J Geetha, research scholar, Calicut University, in a paper read at a recent Women’s Films Seminar at Bangalore). The Mother upholds the dharma which the good son follows. When the ‘bad’ son transgresses it, he is killed.

But the bad son Birju (brilliantly played by Yacub in Aurat) has another and equally important side. He does not suffer patiently the landlord’s extortionism – as the Mother and the ‘good’ son do at least to some extent Birju is not merely a ‘rebel’. He is an ‘outsider’, no respecter of rules. There is a great scene in Aurat. Birju now grown into an illiterate dacoit, raids the moneylender’s house and destroys his account books saying, ‘This is the knowledge that has destroyed us’. That insight anticipates the French philosopher, Foucault by nearly two decades. Foucault remarked how ‘power’ is built around ‘knowledge’and how those outside the charmed circle will always be oppressed. That scene in Aurat has been duplicated in hundreds of films since then. Birju speaks for those who cannot speak – the deprived millions. He is the immortal ‘black’ hero.

Mehboob’s insight in Mother India profoundly affected the style and content of popular cinema. Ganga Jamuna in the 60s, Deewar (with Amitabh Bachchan in the 70s) and Ram Lakhan in the 80s (all hit films) are but inferior variations on Aurat’s theme. To quote Geetha, the Mother’s role is ‘mutated’ in the last two films and she becomes a domestic creature. All the same the basic patterns of Mother India persist today and will do so for a long time.

Roti hammers in Mehboob’s radicalism with even greater force. It analyses the ravages of urban capitalism and contrasts it with a rather idealised tribal life. But the point regarding the dehumanisation of industrialisation with consequent loss of sensuality – even humanity – is well brought out.

Mehboob’s contribution to cinema is so vast that one cannot even begin to do justice to it. He was an untutored genius. Therefore, he saw India with a clear – even ruthless – vision. In that respect he was like the great Urdu fiction writer, Saadat Hasan Manto.

Writers, Poets, Directors

From the 40s onwards a gradual and fruitful collaboration between film writers, poets, and directors emerged in Hindi cinema. The collaboration between Sohrab Modi and Kamal Amrohi was very successful. Modi had a rhetorical, regal approach to history and Amrohi complemented this by his flowery, ornate Urdu dialogue.

A digression is necessary here about the use of language in Hindi cinema. As mentioned earlier, till 1947 even ornate and ornamental Urdu was understood by a section of the masses. Their number gradually declined. In the 1980’s the Persianised dialogue of Amrohi’s Razia Sultan was understood by very few.

All the same the language of the popular ‘Hindi’ cinema has remained robustly Hindustani. From Mother India to Pyaasa to Deewar to the recent hit Maine Pyar Kiya, the dialogue writers have drawn expertly both from Urdu and Hindi. Saleem and Javed, high power film writers, working as a pair, started in the 70s a whole new trend in dialogue in Amitabh Bachchan hits like Sholay. It was macho, it was tough, but it was the pathos of the streets, and at a basic level (stripping away the bravado) also the language of the middle class.

The contribution of cinematic ‘Hindustani’ to national integration has yet to be recognised. The problem is, popular cinema is generally condemned as ‘trash’ without serious analysis.

After Amrohi, came a band of writers, a large number of whom were Muslims and also leftist progressives. They included very different kinds of personalities like KA Abbas, Zia Sarhadi, Abrar Alvi, poets Kaifi Azmi, Sahir Ludhianvi, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Jan Nisar Akhtar and many others. There were two characteristics of this group. Firstly they all came from middle class north Indian Muslim families and were steeped in both Hindi and Urdu cultures and secondly from the early 40s on they were committed leftists – some of them Party members, others active sympathisers.

The achievements of this group which disintegrated by the 70s have not been adequately assessed. As a group the writers brought genuine secularism – a feeling of active togetherness to popular cinema which in those years before TV and video held near complete sway over the collective unconscious. Let’s take a few of them. It was Zia Sarhadi’s spirited dialogue that lent the edge to Mehboob’s radicalism. KA Abbas brought the mix of revlt and romanticism which marks all of Raj Kapoor’s films from Awaara to Bobby. Abrar Alvi created the screen plays which allowed Guru Dutt to shift gradually from the high spirits of Aar Paar to the poetry of defeat of Pyaasa and Kaagaz Ke Phool. Alvi also directed Saheb Bibi Aur Ghulam.

Sahir – the incomparable Sahir, who can ever forget him? His name will live as long as Hindi cinema lives. A complete master of the technique of the classical ghazal and of the film lyric of Hindi greets and bhajans he captured the whole gamut of what Mathew Arnold called ‘the pain of living and the drug of dreams’. He was a visionary and also a caustic observer. See the ‘spread’ of his art in just three songs picked up at random:

‘Yeh takhton ye tajon yeh mehlon ki duniya agar mil bhi jaye to kya hai …’ (This world of thrones, crowns and palaces What avails its gain?)

‘Aaj sajan mohe ang laga lo janam saphal ho jaye …’ (Embrace me, my love make life triumph)

‘Jab amar jhoom ke nachega jab dharti naghme gayegi who subah kabhi to ayegi …’ (The sky will swing and dance, the earth swing Some day that day will come).

There is one name that is as glorious as Sahir’s in Indian cinema – the name of Guru Dutt. It was he who brought one side of the ‘eth’ – its grace, its stoicism, its lyricism, also its self-indulgence – to fine flower in Indian cinema though only one of his films Chaudvin Ka Chand dealt ostensibly with a Muslim family. It was his art, that brought fame and recognition to Alvi and Sahir. In a sense Guru Dutt was the true sangam (confluence) of Hindu and Muslim cultures in cinema.

Actors and performers

Indian cinema is a performance-based cinema. The ‘New Cinema’ in the 60s began a shift towards film as cinematic image/language, but it has not reached out to the masses or even to substantial numbers of the urban middle class. So the actors/performers continue to rule the roast. Here the Muslim contribution has been substantial: Sardar Akhtar (Mother in Aurat), Nargis (Mother in Mother India), Dilip Kumar, Suraiya, Madhubala, Waheeda Rehman, Meena Kumari, Naseeruddin Shah, Shabana Azmi, Aamir Khan and Salman Khan.

Of these, Nargis is unquestionably the greatest actress of our cinema. Her range from the sensuous girl of Aag to the mature role in Mother India is astonishing. The contribution of India’s two greatest director – Raj Kapoor and Mehboob to the shaping of her classic performances should not be forgotten. At the same time, Raj Kapoor’s work is unthinkable without Nargis as is Mother India. In sheer versatility, Dilip Kumar ranks with Nargis. Tragic hero (Andaaz, Devdas) swashbuckler (Azaad) clown (Ram Aur Shyam), none else except Raj Kapoor equals him. Even today in a character role in Kanoon Apna Apna, he brings a thorough professionalism to his performance. Waheeda Rehman broke new ground for women’s roles in Hindi cinema in Pyaasa and Kaagaz Ke Phool.

Under Guru Dutt’s sensitive guidance, she travelled from street woman to comforter to ‘A Star is Born’ role. To see her and Meena Kumari perform in Saheb Bibi Aur Ghulam, to become aware of two great but different styles. Meena Kumari was the epitome of the grace of a dying culture which she lit up in a moment of final glory in Pakeezah.

Naseeruddin Shah and Shabana Azmi are the icons of New Cinema – of a new age, which demands understatement, self parody, ironic posture. Aamir and Salman Khan are icons of a still newer age – the age of post-modernism, all dazzle and glossy surface.

At a different level, comedians Johnny Walker and Mehmood are part of the legend of cinema. A clown has been a ‘must’ in Indian performance arts reaching back to Sanskritic antiquity. Walker and Mehmood brought the Modern Age to an ancient art: Walker in films like Pyaasa not only mimed a semi-inebriate but was the master of throwaway verbal humour. Mehmood had greater variety. He was a ‘body’ comedian who played – sometimes self indulgently – a variety of roles from a lumpen to a South Indian musician.

The Rise and Fall of the Muslim Social

The genre of the ‘Muslim Social’ is an important contribution to Indian cinema. The stylisation started with Pukar. Later it became less legal in films like Dard (of the 40s), Palkhi and numerous other films down to the 70s. Such films dealt with the Muslim North Indian middle class and its social problems spiced with ghazals and qawwalis. The most meaningful of them was Mehboob’s Elan (1947). This became a critique of the ghetto-like quality of certain segments of the Muslim middle class and emphasised the need for education of Muslim youth. The film had another striking feature. It gave a sympathetic portrait of a ‘Western’ wife introduced into a Muslim household. Elan was refreshingly novel here because even today a westernised woman is generally treated as a vamp in Indian cinema.

After Elan the Muslim Social declined into a sentimental, mushy affair. But it remained a popular genre. Guru Dutt made Chaudhvin Ka Chand (about the travails of lovers caught in the trap of ‘mistaken identity’ due to purdah) almost disdainfully to ‘make-up’, as he said, for the losses of Kaagaz ke Phool. But the typical Dutt obsession with frustrated passion raised the film to a notable level. vIn fact the Muslim Social charted the decline of the Muslim ashraf (the gentry) – a feature which comes through movingly despite the hackneyed trappings. In this sense Pakeezah (1971) was the ‘farewell’ film of the Muslim Social. Kamal Amrohi made this story of the tragedy of a courtesan with loving care. He got the period details right (the ashraf or landed gentry culture of Uttar Pradesh in the first half of the century) and the music and lyrics had both the nostalgia for a lost Eden and a lyricism all their own. But what really raised Pakeezah above the normal rut was Meena Kumari’s portrayal of a once gracious culture slowly disintegrating. The performance as well as the film were marvelous swan songs.

After the 70s, the Muslim Social gradually petered out because it no longer met the urgent need of harsher times.

The one film which drove home this message was MS Sathyu’s Garm Hawa released in the early 70s. Though it dealt ostensibly with the travails of a Muslim family in UP at the time of partition, it was really a reflection on the tragedy inflicted on Indian Muslims by the partition. The reflection was a product of bitter post-partition introspection. But it was touched by compassion and humanity.

From Shahenshah to Coolie

In the 70s, a new stereotype began to emerge. This was the common or garden Muslim. He would be a model of loyalty and discipline and when he died it would be with the Kalma (or Proclamation of Faith) on his lips. He no longer talked the flowery Urdu of the Shahenshah and the Nawabs but the patois of the street.

As mentioned earlier, Salim and Javed contributed to the toughening of the language. But Kader Khan as writer and Amjad Khan as the archetypal villain carried it further.

Kader Khan in Muqaddar Ka Sikandar and later on in Coolie introduced a note of religious mysticism. In Muqaddar …, Amitabh Bachchan does not play a ‘Muslim’ role but he evokes the nuances to build up the portrait of a Dervish fulfilling an exalted mission. In Coolie, he portrays a Muslim coolie who becomes a revolutionary. The old Mehboob syndrome of Muslim radicalism is reproduced in Coolie. Amitabh carries a hawk named Allah Rakha on his wrist. This is a direct reference to poet Iqbal’s hawk (Shaheen) a central symbol in his poetry. Shaheen for Iqbal represented the aspiring, soaring spirit of man as in the line. ‘Tu Shaheen hai parwaz hai kaam tera…’ (you are a hawk, your destiny is flight).

Amitabh similarly soared in that film despite its formula trappings. The emotionally charged scene of departing Hajis, the pilgrims sailing to Mecca for the major Muslim festival of Id-ul-Baqr, at Bombay docks is played with a genuine empathy which enfolds the viewer. Coolie represents the rise and integration of the Common Muslim in the working masses of the country rebelling for change.

Facing the harsh 90s

Saeed Akhtar Mirza was part of the New Movement in cinema which rose to prominence from the late 60s onwards. His work has always been marked by an ‘adversary element’, meaning a critique of the status from a radical point of view. Arvind Desai Ki Ajeeb Dastan was a look at the frustrations of an idealistic youth caught in the trap of a feudal money culture, Albert Pinto Ko Gussa Kyon Aata Hai was a look both at the problem of class and ethnic identifications. Then followed tele-serials, the most notable being Nukkad (street corner). Here Mirza looked at the rising industrial urban culture from the worm’s point of view – the lower middle class of various communities buffeted by changes in the world above clinging to lost vestiges of dignity and meaning in life. It was one of the two or three outstanding tele-serials of the last decade. In fact, it was a cultural phenomenon.

In his Salim Langde Pe Mat Ro he examines the problems of Muslim lumpens in central Bombay. The film won the best Hindi film National Award for 1990.

What is impressive about the film is the multi-layered approach to the subject. It rises beyond its specific city and class and becomes a probing into the condition of Indian Muslims. The gradual economic and educational decline of urban Muslims is portrayed. Also the shift of the young to crime, a flight from a society which they feel rejects them. The problems of communalism, ghetto mentality, and search for an ethnic identity which does not clash with a national identity are also explored.

Salim reminds one of the French director Maurice Pialat’s film Police which deals with the problems of Algerians in Paris. Salim is a complex and reflective work which in itself is a search for identity. Indian Muslims have find a place in the increasingly metropolitan culture of India.

Salim is an extremely sensitive and intelligent attempt to depict this cultural process. It says there are no easy answers but it also opens up ways of resolving the crisis.

Muslim Contribution to Cinema – An Attempt at Harmony

To sum up: It’s a long journey from Pukar, to Salim Langde …. But it’s a splendid, coruscating one providing spectacle, beauty, wit, tragedy, high spirits – and a clear sighted introspection. It’s a rich mosaic of meaning, song and dance without which Indian cinema – in fact Indian culture – would be incomplete.

In one word the Muslim contribution to cinema is: Harmony.

In arrangement with Seminar on ‘Pluralism and Democracy in Bollywood’ organised by Teesta Setalvad

There is another important aspect of Indian cinema. It caters to the needs of a population dazzlingly diverse in language, religion and culture. Today what is called the ‘regional’ cinema is as important as Hindi cinema. But Hindi cinema (with which this article will be concerned) was the primary source of themes and styles at least till the late 70s. It was in the domain of popular cinema that the diverse cultures of India met and negotiated their differences. They did not merge but they worked in harmony. In fact ‘harmony’ is the key world in India cinema. It is the one Indian cultural-industrial structure which has resisted separatism. It’s because of this element that Indian cinema has become over the past 50 years – despite its many distortions and contractions – a major instrument of national consolidation – a true unity in diversity. MIDBANNER To this ‘unity diversity’ the Muslim ethos in India has made a notable contribution.

What is the ‘Muslim ethos’ in India? Very briefly, one can answer this question at two levels:

a) ‘Classical’ or high culture – a mix of Arabic-Perso-Turkish elements in historical work, fiction, music and painting such as in the work of poets and novelists like Ghalib, (or today Ms Qurratulain Hyder), artists like Abdur Rahman Chughtai, or the Ustads in the field of music.

b) At a popular or folk level, the work of Urdu dramatists like Aga Hashr Kashmiri used in popular theatre of the 1930s; the Nautanki Folk-theatre culture of Uttar Pradesh, compounded of mythological and folk tales rendered in song-dance and rustic revues in a mix of ornate Urdu and dialect Hindi of north India; and the rich Qawwali musical tradition, sufic in origin and retaining traces of devotional and ecstatic singing today.

As far as cinema is concerned, both these influences are important. The Muslim ethos in Indian cinema was not represented by ‘Muslim’ artists alone. A host of non-Muslims like Sohrab Modi, Guru Dutt or Shyam Benegal can well claim to be part of the ‘Muslim’ ethos of north India. There was, and is, certainly a ‘Muslim’ ethos of Bengal and South India which is equally important. But that deserves fuller treatment elsewhere.

The point is that in the popular entertainment genre par excellence – cinema – the ‘Muslim ethos’ was an important element since the 1930s – the coming of sound. It diminished after 1947 but remains an important element today. In fact the persistence of the ‘Muslim ethos’ in Indian cinema today is one of the most hopeful signs of Indian secularism. Manmohan Desai, prolific maker of film hits and part creator of the Amitabh Bachchan legend (the superstar of the 70s who signified the new angry hero culture) has said in a recorded discussion: If the Muslims don’t like a film it flops’.

One of the most important elements of the Indian film is music. A great music director, Naushad, brought both the vigour of Uttar Pradesh’s folk music and the grace of the old UP Nawab Courts to his immortal music of the 40s and 50s. The dialogue of the 30s and 40s ‘Muslim socials’ was in Persianised Urdu but even in ‘Hindi’ films today the dialogue is in Hindustani – perhaps the only place where this ‘language’ is practiced with ease and confidence.

In this matrix of music and dialogue, ‘high’ and ‘popular’ Muslim cultures come together. As late as the 60s, a film villain traps a heroine by using a disguise and quoting Ghalib: ‘Badal kar faqiron ka hum bhes …’ Ghalib/‘Tamashai-I-abl-I-karam dekhte hain …’ (we put on the garb of a beggar to test the generosity of the rich). The audience understood and applauded the quote.

Today this delicate irony may not be understood. But in the ’80s this last couplet of Sahir Ludhianvi sung in a film called Laxmi went to the heart of the audience: ‘Halat se ladna mushkil tha balat se rishta jod liya/ Jis raat ki koi subha nahin us raat se rishta jod liya…’. (I could not fight circumstances I compromised/I made a pact with endless night). The couplet lit up the films; it also seemed like an epitaph on Sahir.

I take these two examples to illustrate the Muslim ‘ethos’ which E.M. Forster once described as an ‘attitude towards life both exquisite and durable’. This attitude is denoted by a cultural elegance, irony, stoicism, a throw away humour, and what is called ‘grace under pressure’. Certainly such an attitude could be trivialised. But supreme artists like Dilip Kumar, Meena Kumari, Nargis and Shabana Azmi brought to this attitude a meaning and individuality of their own.

It would be appropriate at this stage to look at the Muslim ethos in a chronological fashion modified by the need to pursue specific trends back and forth across decades.

Devdas – Entry of the Laila – Majnu Myth

The first dominant note of the Muslim ethos was struck not in any specific Muslim film or by a Muslim director but in the film Devdas directed by PC Barua (1935) based on a novel by Sarat Chandra Chatterji (1917). This tale of two small town lovers torn apart by caste and class has haunted Indian cinema down the decades up to date. There are two elements in Indian cinema well analysed in another context by psychiatrists Sudhir Kakar and John M Ross in Tales of Love, Sex and Danger (OUP 1986) as the Radha-Krishna and Laila-Majnu traditions. Radha and Krishna are the divine lovers in human form in Hindu mythology, and Laila and Majnu are passionate but doomed lovers in Arabic and Persian folklore and literature.

The Radha-Krishna tradition, say the authors, is an evocation and elaboration of here-and-now passion, an attempt to catch the exciting fleeting moment of the senses, not tragic but tender and ultimately cheerful. In the Laila-Majnu tradition, love is the ‘essential desire of God; earthly love is but a preparation for the heavenly acme; the challenge to rights of older and powerful men to dispose of and control female sexuality; the utter devotion of the women lovers to the man unto death; loving in secrecy and concealment, yet without shame or guilt’.

Both the elements are fused in Devdas. The Radha-Krishna element dominates the first half; the Laila-Majnu element the second. There are two features common to both traditions. The love is not ‘spiritual’ love but sexual love raised to a spiritual plane. Secondly, to quote the 13th Century Persian mystic poet, Rumi: ‘The house of love has doors and roofs made of music, melody and poetry’. This is the distinctive contribution of the Muslim ethos to Indian cinema – the mix of Rumi’s three elements. You can go from Devdas to Barsaat in the ’40s or Pyaasa in the ’50s; Chaudvin Ka Chand in the ’60s; Pakeezah in the ’70s; Sagar (with Kamal Hasan, Dimple Kapadia, and Rishi Kapoor) in the ’80s. There is the same hunting mix of the two great religious-cultural traditions of our land.

Pukar – The Rise of the Shahenshah film

Pukar (1939) directed by Sohrab Modi with dialogues by Kamal Amrohi was the first notable ‘Muslim social film’. It was cast, no doubt in the Shahenshah (King of Kings) framework. Mughal emperor Jehangir, whose queen Noor Jehan has accidentally killed a washerman with an arrow, is faced with a demand for retributive justice by the widow. The emperor himself should be killed so that the queen be widowed.

Today Pukar looks dated and rhetorical. Yet it is important to isolate some elements which continue to surface in one form or another in the coming decades, from the 40s to the present. One was the idealisation of ‘Muslim’ rulership as one based on equal partnership with non-Muslims (even of the lesser castes) and a rough-and-ready Rule of Law. The roots of the archetype of task a ‘rough diamond’ were created – though in the film the Muslims and their ‘partners’ the Rajputs were anything but rough. The basic ideal was one of directness of approach of life.

A second element was the elegance of speech and surroundings which became a marked feature of Muslim social’ – meaning films dealing with Muslim families and social problems which will be dealt with later.

A third element was the stress laid on Hindu-Muslim ‘harmony’. Jehangir’s Prime Minister is a Rajput who fiercely guards his independence.

Another Shahenshah film was K Asif’s Mughal-e-Azam (The Grand Mughal). In a sense it’s an extension of the Pukar syndrome. The legendary love of court dancer Anarkali for Prince Jehangir, the great Emperor Akbar’s son, has elements of mystical passion in it. Akbar, played with rhetorical flourish by Prithviraj Kapoor, represents the ‘needs of the State’ which triumphs over love. The film is not a ‘classical’ work but a massive cultural artefact made unforgettable by the splendiferous sets and the majestic singing of the classical maestro Bade Gulam Ali Khan.

Mehboob – The Rise of Radicalism

Filmmaker Mehboob Khan sprang from the soil of Gujarat and his early work possessed both the rawness and the strength of Mother Earth. The evocation of the cycle of seasons, the beauty of the long bullock cart caravans, the sensuality of the women and the depiction of the brutal strength both of nature and human oppression came spontaneously to him.

Mehboob made a large number of films on diverse subjects – social, romance etc. But, in my opinion, his major contribution to films rests on three films – Aurat (1940) later remade as Mother India (1957) and Roti (1942).

Aurat/Mother India, is, of course, the seminal film of India cinema. It is reckoned that Mother India runs every day in some theatre in some part of India. What accounts for its success?

There are elements in the films which go deep into the Indian psyche and touch a chord which no one has ever touched before or since. It would be simplistic to call it ‘patriotism’. It is the summoning up of an entire ambience – the ambience of the ‘lost’ India for millions of urbanites, a call to Indians from their past – not a noble past but a credible and genuine past.

Mehboob gave the archetypal ‘Mother’ myth to India cinema. She is not an a sexual but a full blooded woman and equal partner in her husband’s labours (a point acutely noted by J Geetha, research scholar, Calicut University, in a paper read at a recent Women’s Films Seminar at Bangalore). The Mother upholds the dharma which the good son follows. When the ‘bad’ son transgresses it, he is killed.

But the bad son Birju (brilliantly played by Yacub in Aurat) has another and equally important side. He does not suffer patiently the landlord’s extortionism – as the Mother and the ‘good’ son do at least to some extent Birju is not merely a ‘rebel’. He is an ‘outsider’, no respecter of rules. There is a great scene in Aurat. Birju now grown into an illiterate dacoit, raids the moneylender’s house and destroys his account books saying, ‘This is the knowledge that has destroyed us’. That insight anticipates the French philosopher, Foucault by nearly two decades. Foucault remarked how ‘power’ is built around ‘knowledge’and how those outside the charmed circle will always be oppressed. That scene in Aurat has been duplicated in hundreds of films since then. Birju speaks for those who cannot speak – the deprived millions. He is the immortal ‘black’ hero.

Mehboob’s insight in Mother India profoundly affected the style and content of popular cinema. Ganga Jamuna in the 60s, Deewar (with Amitabh Bachchan in the 70s) and Ram Lakhan in the 80s (all hit films) are but inferior variations on Aurat’s theme. To quote Geetha, the Mother’s role is ‘mutated’ in the last two films and she becomes a domestic creature. All the same the basic patterns of Mother India persist today and will do so for a long time.

Roti hammers in Mehboob’s radicalism with even greater force. It analyses the ravages of urban capitalism and contrasts it with a rather idealised tribal life. But the point regarding the dehumanisation of industrialisation with consequent loss of sensuality – even humanity – is well brought out.

Mehboob’s contribution to cinema is so vast that one cannot even begin to do justice to it. He was an untutored genius. Therefore, he saw India with a clear – even ruthless – vision. In that respect he was like the great Urdu fiction writer, Saadat Hasan Manto.

Writers, Poets, Directors

From the 40s onwards a gradual and fruitful collaboration between film writers, poets, and directors emerged in Hindi cinema. The collaboration between Sohrab Modi and Kamal Amrohi was very successful. Modi had a rhetorical, regal approach to history and Amrohi complemented this by his flowery, ornate Urdu dialogue.

A digression is necessary here about the use of language in Hindi cinema. As mentioned earlier, till 1947 even ornate and ornamental Urdu was understood by a section of the masses. Their number gradually declined. In the 1980’s the Persianised dialogue of Amrohi’s Razia Sultan was understood by very few.

All the same the language of the popular ‘Hindi’ cinema has remained robustly Hindustani. From Mother India to Pyaasa to Deewar to the recent hit Maine Pyar Kiya, the dialogue writers have drawn expertly both from Urdu and Hindi. Saleem and Javed, high power film writers, working as a pair, started in the 70s a whole new trend in dialogue in Amitabh Bachchan hits like Sholay. It was macho, it was tough, but it was the pathos of the streets, and at a basic level (stripping away the bravado) also the language of the middle class.

The contribution of cinematic ‘Hindustani’ to national integration has yet to be recognised. The problem is, popular cinema is generally condemned as ‘trash’ without serious analysis.

After Amrohi, came a band of writers, a large number of whom were Muslims and also leftist progressives. They included very different kinds of personalities like KA Abbas, Zia Sarhadi, Abrar Alvi, poets Kaifi Azmi, Sahir Ludhianvi, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Jan Nisar Akhtar and many others. There were two characteristics of this group. Firstly they all came from middle class north Indian Muslim families and were steeped in both Hindi and Urdu cultures and secondly from the early 40s on they were committed leftists – some of them Party members, others active sympathisers.

The achievements of this group which disintegrated by the 70s have not been adequately assessed. As a group the writers brought genuine secularism – a feeling of active togetherness to popular cinema which in those years before TV and video held near complete sway over the collective unconscious. Let’s take a few of them. It was Zia Sarhadi’s spirited dialogue that lent the edge to Mehboob’s radicalism. KA Abbas brought the mix of revlt and romanticism which marks all of Raj Kapoor’s films from Awaara to Bobby. Abrar Alvi created the screen plays which allowed Guru Dutt to shift gradually from the high spirits of Aar Paar to the poetry of defeat of Pyaasa and Kaagaz Ke Phool. Alvi also directed Saheb Bibi Aur Ghulam.

Sahir – the incomparable Sahir, who can ever forget him? His name will live as long as Hindi cinema lives. A complete master of the technique of the classical ghazal and of the film lyric of Hindi greets and bhajans he captured the whole gamut of what Mathew Arnold called ‘the pain of living and the drug of dreams’. He was a visionary and also a caustic observer. See the ‘spread’ of his art in just three songs picked up at random:

‘Yeh takhton ye tajon yeh mehlon ki duniya agar mil bhi jaye to kya hai …’ (This world of thrones, crowns and palaces What avails its gain?)

‘Aaj sajan mohe ang laga lo janam saphal ho jaye …’ (Embrace me, my love make life triumph)

‘Jab amar jhoom ke nachega jab dharti naghme gayegi who subah kabhi to ayegi …’ (The sky will swing and dance, the earth swing Some day that day will come).

There is one name that is as glorious as Sahir’s in Indian cinema – the name of Guru Dutt. It was he who brought one side of the ‘eth’ – its grace, its stoicism, its lyricism, also its self-indulgence – to fine flower in Indian cinema though only one of his films Chaudvin Ka Chand dealt ostensibly with a Muslim family. It was his art, that brought fame and recognition to Alvi and Sahir. In a sense Guru Dutt was the true sangam (confluence) of Hindu and Muslim cultures in cinema.

Actors and performers

Indian cinema is a performance-based cinema. The ‘New Cinema’ in the 60s began a shift towards film as cinematic image/language, but it has not reached out to the masses or even to substantial numbers of the urban middle class. So the actors/performers continue to rule the roast. Here the Muslim contribution has been substantial: Sardar Akhtar (Mother in Aurat), Nargis (Mother in Mother India), Dilip Kumar, Suraiya, Madhubala, Waheeda Rehman, Meena Kumari, Naseeruddin Shah, Shabana Azmi, Aamir Khan and Salman Khan.

Of these, Nargis is unquestionably the greatest actress of our cinema. Her range from the sensuous girl of Aag to the mature role in Mother India is astonishing. The contribution of India’s two greatest director – Raj Kapoor and Mehboob to the shaping of her classic performances should not be forgotten. At the same time, Raj Kapoor’s work is unthinkable without Nargis as is Mother India. In sheer versatility, Dilip Kumar ranks with Nargis. Tragic hero (Andaaz, Devdas) swashbuckler (Azaad) clown (Ram Aur Shyam), none else except Raj Kapoor equals him. Even today in a character role in Kanoon Apna Apna, he brings a thorough professionalism to his performance. Waheeda Rehman broke new ground for women’s roles in Hindi cinema in Pyaasa and Kaagaz Ke Phool.

Under Guru Dutt’s sensitive guidance, she travelled from street woman to comforter to ‘A Star is Born’ role. To see her and Meena Kumari perform in Saheb Bibi Aur Ghulam, to become aware of two great but different styles. Meena Kumari was the epitome of the grace of a dying culture which she lit up in a moment of final glory in Pakeezah.

Naseeruddin Shah and Shabana Azmi are the icons of New Cinema – of a new age, which demands understatement, self parody, ironic posture. Aamir and Salman Khan are icons of a still newer age – the age of post-modernism, all dazzle and glossy surface.

At a different level, comedians Johnny Walker and Mehmood are part of the legend of cinema. A clown has been a ‘must’ in Indian performance arts reaching back to Sanskritic antiquity. Walker and Mehmood brought the Modern Age to an ancient art: Walker in films like Pyaasa not only mimed a semi-inebriate but was the master of throwaway verbal humour. Mehmood had greater variety. He was a ‘body’ comedian who played – sometimes self indulgently – a variety of roles from a lumpen to a South Indian musician.

The Rise and Fall of the Muslim Social

The genre of the ‘Muslim Social’ is an important contribution to Indian cinema. The stylisation started with Pukar. Later it became less legal in films like Dard (of the 40s), Palkhi and numerous other films down to the 70s. Such films dealt with the Muslim North Indian middle class and its social problems spiced with ghazals and qawwalis. The most meaningful of them was Mehboob’s Elan (1947). This became a critique of the ghetto-like quality of certain segments of the Muslim middle class and emphasised the need for education of Muslim youth. The film had another striking feature. It gave a sympathetic portrait of a ‘Western’ wife introduced into a Muslim household. Elan was refreshingly novel here because even today a westernised woman is generally treated as a vamp in Indian cinema.

After Elan the Muslim Social declined into a sentimental, mushy affair. But it remained a popular genre. Guru Dutt made Chaudhvin Ka Chand (about the travails of lovers caught in the trap of ‘mistaken identity’ due to purdah) almost disdainfully to ‘make-up’, as he said, for the losses of Kaagaz ke Phool. But the typical Dutt obsession with frustrated passion raised the film to a notable level. vIn fact the Muslim Social charted the decline of the Muslim ashraf (the gentry) – a feature which comes through movingly despite the hackneyed trappings. In this sense Pakeezah (1971) was the ‘farewell’ film of the Muslim Social. Kamal Amrohi made this story of the tragedy of a courtesan with loving care. He got the period details right (the ashraf or landed gentry culture of Uttar Pradesh in the first half of the century) and the music and lyrics had both the nostalgia for a lost Eden and a lyricism all their own. But what really raised Pakeezah above the normal rut was Meena Kumari’s portrayal of a once gracious culture slowly disintegrating. The performance as well as the film were marvelous swan songs.

After the 70s, the Muslim Social gradually petered out because it no longer met the urgent need of harsher times.

The one film which drove home this message was MS Sathyu’s Garm Hawa released in the early 70s. Though it dealt ostensibly with the travails of a Muslim family in UP at the time of partition, it was really a reflection on the tragedy inflicted on Indian Muslims by the partition. The reflection was a product of bitter post-partition introspection. But it was touched by compassion and humanity.

From Shahenshah to Coolie

In the 70s, a new stereotype began to emerge. This was the common or garden Muslim. He would be a model of loyalty and discipline and when he died it would be with the Kalma (or Proclamation of Faith) on his lips. He no longer talked the flowery Urdu of the Shahenshah and the Nawabs but the patois of the street.

As mentioned earlier, Salim and Javed contributed to the toughening of the language. But Kader Khan as writer and Amjad Khan as the archetypal villain carried it further.

Kader Khan in Muqaddar Ka Sikandar and later on in Coolie introduced a note of religious mysticism. In Muqaddar …, Amitabh Bachchan does not play a ‘Muslim’ role but he evokes the nuances to build up the portrait of a Dervish fulfilling an exalted mission. In Coolie, he portrays a Muslim coolie who becomes a revolutionary. The old Mehboob syndrome of Muslim radicalism is reproduced in Coolie. Amitabh carries a hawk named Allah Rakha on his wrist. This is a direct reference to poet Iqbal’s hawk (Shaheen) a central symbol in his poetry. Shaheen for Iqbal represented the aspiring, soaring spirit of man as in the line. ‘Tu Shaheen hai parwaz hai kaam tera…’ (you are a hawk, your destiny is flight).

Amitabh similarly soared in that film despite its formula trappings. The emotionally charged scene of departing Hajis, the pilgrims sailing to Mecca for the major Muslim festival of Id-ul-Baqr, at Bombay docks is played with a genuine empathy which enfolds the viewer. Coolie represents the rise and integration of the Common Muslim in the working masses of the country rebelling for change.

Facing the harsh 90s

Saeed Akhtar Mirza was part of the New Movement in cinema which rose to prominence from the late 60s onwards. His work has always been marked by an ‘adversary element’, meaning a critique of the status from a radical point of view. Arvind Desai Ki Ajeeb Dastan was a look at the frustrations of an idealistic youth caught in the trap of a feudal money culture, Albert Pinto Ko Gussa Kyon Aata Hai was a look both at the problem of class and ethnic identifications. Then followed tele-serials, the most notable being Nukkad (street corner). Here Mirza looked at the rising industrial urban culture from the worm’s point of view – the lower middle class of various communities buffeted by changes in the world above clinging to lost vestiges of dignity and meaning in life. It was one of the two or three outstanding tele-serials of the last decade. In fact, it was a cultural phenomenon.

In his Salim Langde Pe Mat Ro he examines the problems of Muslim lumpens in central Bombay. The film won the best Hindi film National Award for 1990.

What is impressive about the film is the multi-layered approach to the subject. It rises beyond its specific city and class and becomes a probing into the condition of Indian Muslims. The gradual economic and educational decline of urban Muslims is portrayed. Also the shift of the young to crime, a flight from a society which they feel rejects them. The problems of communalism, ghetto mentality, and search for an ethnic identity which does not clash with a national identity are also explored.

Salim reminds one of the French director Maurice Pialat’s film Police which deals with the problems of Algerians in Paris. Salim is a complex and reflective work which in itself is a search for identity. Indian Muslims have find a place in the increasingly metropolitan culture of India.

Salim is an extremely sensitive and intelligent attempt to depict this cultural process. It says there are no easy answers but it also opens up ways of resolving the crisis.

Muslim Contribution to Cinema – An Attempt at Harmony

To sum up: It’s a long journey from Pukar, to Salim Langde …. But it’s a splendid, coruscating one providing spectacle, beauty, wit, tragedy, high spirits – and a clear sighted introspection. It’s a rich mosaic of meaning, song and dance without which Indian cinema – in fact Indian culture – would be incomplete.

In one word the Muslim contribution to cinema is: Harmony.

In arrangement with Seminar on ‘Pluralism and Democracy in Bollywood’ organised by Teesta Setalvad

—Iqbal Masud

URL: http://www.screenindia.com/fullstory.php?content_id=9980